Post by UKarchaeology on Aug 11, 2015 18:54:50 GMT

Buried by Vesuvius nearly 2,000 years ago, archaeologists at Herculaneum have excavated and carried out the first-ever full reconstruction of the timber roof of a Roman villa

For almost two millennia, the piles of wood lay undisturbed and largely intact under layers of hardened volcanic material. Now, after three years of painstaking work, archaeologists at Herculaneum have not only excavated and preserved the pieces, but worked out how they fitted together, achieving the first-ever full reconstruction of the timberwork of a Roman roof.

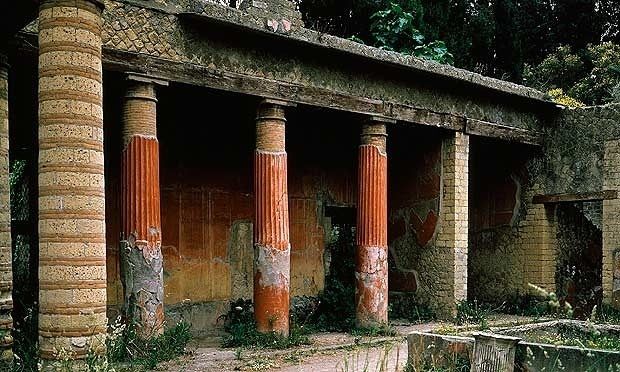

With several dozen rooms, the House of the Telephus Relief was "top-level Roman real estate", said Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, the director of the Herculaneum Conservation Project (HCP). It was more of a palace or mansion, thought to have been built for Marcus Nonius Balbus, the Roman governor of Crete and part of modern-day Libya, whose ostentatious tomb was found nearby.

The most lavishly decorated part of the immense residence was a three-storey tower. On the top floor was a nine-metre high dining room with a coloured marble floor and walls, a suspended ceiling and a wrap-around terrace. It offered the owners and their dinner guests a heart-stopping view across the silver-blue Bay of Naples to the islands of Ischia and Capri.

And now it is providing the archaeologists of Wallace-Hadrill's project with one of their most exciting finds: the timber roof of the Roman villa. "It is not unheard of for bits of roofs from the classical world to survive," said Wallace-Hadrill. "But it is incredibly rare."

What his archaeologists uncovered, however, was something altogether more comprehensive – almost 250 pieces, which they were able to piece together. "It's the first-ever full reconstruction of the timberwork of a Roman roof," said Wallace-Hadrill.

In 79AD the owners of the House of the Telephus Relief – possibly Marcus Nonius Balbus's descendants – would have had every reason to feel serenely confident of their future wealth and welfare. But on or about 24 August that year Vesuvius – clearly visible from the back of the mansion – erupted and released as much thermal energy as 100,000 Hiroshima bombs.

On the first day Herculaneum was unaffected. But on the second, the pillar of smoke and ash collapsed, the wind changed direction and a 400C pyroclastic surge swept through the town, instantly killing everyone from the lowliest slave to the owners of the great house by the shore.

One thousand, nine hundred and thirty years later, archaeologists were digging on what – until the eruption – was the beach, funded by the Packard Humanities Institute, the brainchild of a computer heir. Unlike nearby Pompeii, Herculaneum was buried under volcanic matter that hardened.

"Sometimes you need to use pneumatic drills," said the project's chief archaeologist, Domenico Camardo. Gradually, he and the other archaeologists uncovered first the beams of the roof and then smaller pieces. "It was incredible, because what we were discovering was living wood."

From the way in which the pieces lay his team was able to establish that the roof of the House of the Telephus Relief had been swept off by the pyroclastic surge, turned upside down and then smashed on to the beach. The timberwork was embedded in wet sand, which can preserve wood for centuries, and was then smothered with what soon became an air-tight layer of rock – a freak combination of circumstances that has produced a unique result.

"They have been able to calculate the exact pitch of the roof from the angle of the joinery and work out how every single bit fitted together," said Wallace-Hadrill.

What is more, entire panels from the ceiling, which is thought to have been suspended inside the roof, have survived. Some even bear traces of original paint and gold leaf with which they were decorated.

The panels, together with the parts of the roof, have been scanned, photographed and put into a refrigerated container to conserve them. Wallace-Hadrill hopes techniques can be identified that will allow the panels to be transported and displayed at an exhibition on Pompeii and Herculaneum next year at the British Museum.

In the meantime, the archaeologists are trying to reconstruct the pattern of the ceiling, which they believe echoed that of the top-floor dining room's dazzling floor, containing 36 different sorts of marble from every corner of the Mediterranean basin. Already, they know the ceiling was what Camardo calls "a triumph of colour – almost too much for the taste of today".

The other striking thing about it is how closely its design resembles those of the panelled ceilings of Renaissance palazzi , which can be seen all over Italy to this day.

Until now it had been thought the earliest wooden coffered ceilings were made in France in the early Renaissance. But the panels retrieved from the beach at Herculaneum prove otherwise. "Renaissance architects reinvented the concept, unaware the Romans got there first," said Camardo.

(source/pic: www.theguardian.com/science/2012/jul/23/house-telephus-relief-roman?INTCMP=SRCH )

For almost two millennia, the piles of wood lay undisturbed and largely intact under layers of hardened volcanic material. Now, after three years of painstaking work, archaeologists at Herculaneum have not only excavated and preserved the pieces, but worked out how they fitted together, achieving the first-ever full reconstruction of the timberwork of a Roman roof.

With several dozen rooms, the House of the Telephus Relief was "top-level Roman real estate", said Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, the director of the Herculaneum Conservation Project (HCP). It was more of a palace or mansion, thought to have been built for Marcus Nonius Balbus, the Roman governor of Crete and part of modern-day Libya, whose ostentatious tomb was found nearby.

The most lavishly decorated part of the immense residence was a three-storey tower. On the top floor was a nine-metre high dining room with a coloured marble floor and walls, a suspended ceiling and a wrap-around terrace. It offered the owners and their dinner guests a heart-stopping view across the silver-blue Bay of Naples to the islands of Ischia and Capri.

And now it is providing the archaeologists of Wallace-Hadrill's project with one of their most exciting finds: the timber roof of the Roman villa. "It is not unheard of for bits of roofs from the classical world to survive," said Wallace-Hadrill. "But it is incredibly rare."

What his archaeologists uncovered, however, was something altogether more comprehensive – almost 250 pieces, which they were able to piece together. "It's the first-ever full reconstruction of the timberwork of a Roman roof," said Wallace-Hadrill.

In 79AD the owners of the House of the Telephus Relief – possibly Marcus Nonius Balbus's descendants – would have had every reason to feel serenely confident of their future wealth and welfare. But on or about 24 August that year Vesuvius – clearly visible from the back of the mansion – erupted and released as much thermal energy as 100,000 Hiroshima bombs.

On the first day Herculaneum was unaffected. But on the second, the pillar of smoke and ash collapsed, the wind changed direction and a 400C pyroclastic surge swept through the town, instantly killing everyone from the lowliest slave to the owners of the great house by the shore.

One thousand, nine hundred and thirty years later, archaeologists were digging on what – until the eruption – was the beach, funded by the Packard Humanities Institute, the brainchild of a computer heir. Unlike nearby Pompeii, Herculaneum was buried under volcanic matter that hardened.

"Sometimes you need to use pneumatic drills," said the project's chief archaeologist, Domenico Camardo. Gradually, he and the other archaeologists uncovered first the beams of the roof and then smaller pieces. "It was incredible, because what we were discovering was living wood."

From the way in which the pieces lay his team was able to establish that the roof of the House of the Telephus Relief had been swept off by the pyroclastic surge, turned upside down and then smashed on to the beach. The timberwork was embedded in wet sand, which can preserve wood for centuries, and was then smothered with what soon became an air-tight layer of rock – a freak combination of circumstances that has produced a unique result.

"They have been able to calculate the exact pitch of the roof from the angle of the joinery and work out how every single bit fitted together," said Wallace-Hadrill.

What is more, entire panels from the ceiling, which is thought to have been suspended inside the roof, have survived. Some even bear traces of original paint and gold leaf with which they were decorated.

The panels, together with the parts of the roof, have been scanned, photographed and put into a refrigerated container to conserve them. Wallace-Hadrill hopes techniques can be identified that will allow the panels to be transported and displayed at an exhibition on Pompeii and Herculaneum next year at the British Museum.

In the meantime, the archaeologists are trying to reconstruct the pattern of the ceiling, which they believe echoed that of the top-floor dining room's dazzling floor, containing 36 different sorts of marble from every corner of the Mediterranean basin. Already, they know the ceiling was what Camardo calls "a triumph of colour – almost too much for the taste of today".

The other striking thing about it is how closely its design resembles those of the panelled ceilings of Renaissance palazzi , which can be seen all over Italy to this day.

Until now it had been thought the earliest wooden coffered ceilings were made in France in the early Renaissance. But the panels retrieved from the beach at Herculaneum prove otherwise. "Renaissance architects reinvented the concept, unaware the Romans got there first," said Camardo.

(source/pic: www.theguardian.com/science/2012/jul/23/house-telephus-relief-roman?INTCMP=SRCH )